Testimony from the 2022 Russian exodus

The following piece is based on an interview with a North Caucasian citizen, referred to as Mark. He escaped Russia with his friend and business partner, Alexey.

On the 21st of September 2022, seven months into the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the Kremlin decided to order a “partial mobilization” to replenish its depleted forces. What at first was supposed to be a blitzkrieg – blowing through Ukraine’s army in a matter of days – quickly turned into a costly and embarrassing quagmire, forcing Putin to enlist an additional 300,000 troops. The ensuing exodus of hundreds of thousands of Russians to neighboring countries made headlines worldwide. [1]

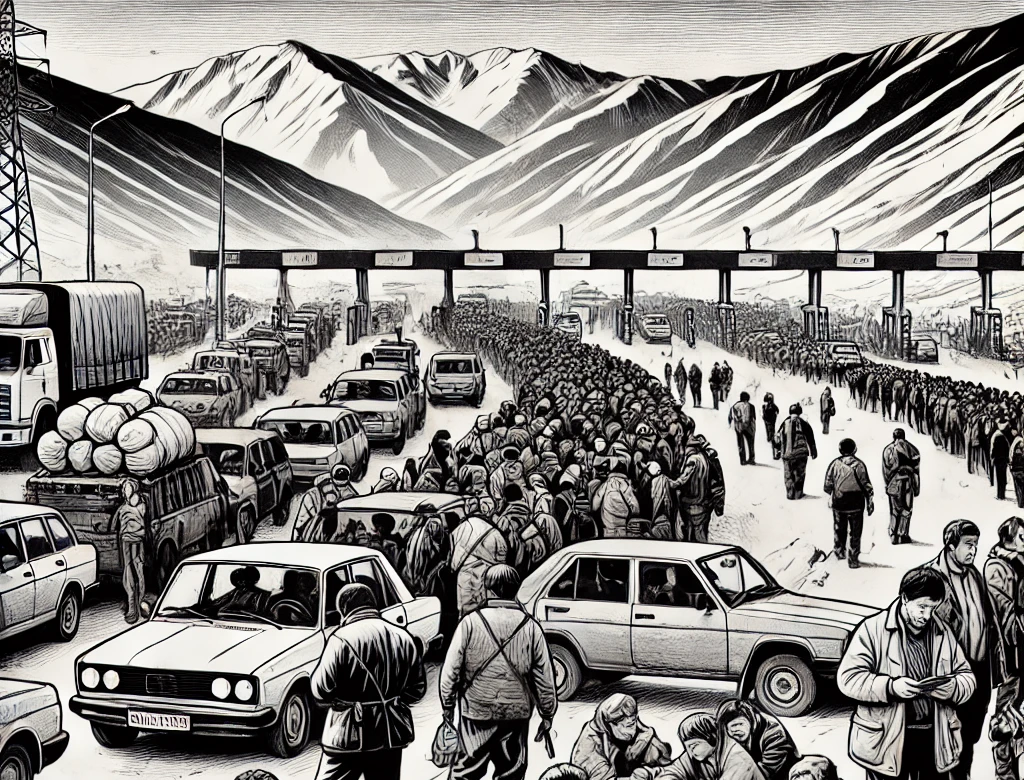

One border crossing in particular, Verkhny Lars, between Russia and Georgia, quickly caught international attention for its chaos: endless traffic jams, entire families on foot, companions sharing meager stews cooked in beaten-up aluminum pots on cold asphalt, of entire lives crammed into bloated suitcases. [2]

Is their plight retribution for not standing up to Putin’s war or are they mere innocents escaping mobilization? The truth, as always, lies somewhere in between. I interviewed one such individual, whose fateful experience could help us see the human side of this event. Speaking from his new home in Germany, Mark, from the regional north Caucasian town of Nalchik in the Russian Federation, recounts his experience. We had exchanged a few messages beforehand to have a better understanding of the interview’s purpose. In our online discussion, I quickly understood the dos and don’ts during the planned call. Chiefly that being in the Russian federation does not equate to being Russian, Mark was greatly insistent on that point (note that I mentioned his town was in the “Russian federation”, not “in Russia”, a more acceptable phrasing for him). In hindsight, I understand why.

Since the end of the 18th century, tsarist Russia of Peter I the Great had designated North Caucasus as a Russian province. At the crossroad between Russia, the Ottoman and Persian empires, the area was always greatly contested. By 1864, the Circassian people, an ethnic group from the Caucasus northwest, was defeated by tsar Alexander II after nearly a hundred years of struggle. Although the reformist tsar made a number of sweeping reforms to the state – modernizing the military, reducing censorship as well as abolishing serfdom; he enacted forced resettlement and expulsions of Circassians and replaced them by Cossacks and ethnic Russians [3]. Some 400,000 Circassians emigrated to the neighboring Ottoman empire, with many thousands dying of starvation and sickness en route [4]. Unfortunately, this tragic event was just the beginning of their suffering. The disastrous population transfers and deportations under Soviet rule were soon to follow. The deep wounds of the past two centuries remain open to this day in the region, not helped by Russia’s constant denial of local history at public schools. Moscow sporadically adds insult to injury, as seen in 2015 in Sochi (part of Circassia) by erecting a monument to the tsar, bewildering the local population [5]. In light of such history, one can better understand the deep resentment Mark expressed towards the central power: “when you are non-russian in the russian federation, it is not easy because they always dehumanize you” he said, adding that “we are only Russians when it’s convenient for them”. His view however is far from representing a minority in the federation. A 2010 census listed over 193 ethnic groups, most sharing a tumultuous relationship with Moscow. Additionally, the toppling of unpopular regimes around the old continent in Ukraine and in Arab countries during the Arab spring, led Putin to fixate on the threat of a so-called “color revolution”. Conspiratorial to its core, those uprisings are believed to be instigated by westerner powers to undermine Moscow’s clout [6]. This fear of revolts coupled with the nostalgia of a past imperial grandeur can explain Moscow’s 20 years of influence, annexation and war against its neighbors.

It is in this environment, during the late agonizing years of the Soviet Union that Mark was brought up. After his musical studies, he felt the need to explore his region to discover its rich folkloric traditions. With the creation of an independent label, he traveled across this mountainous region to record these aging artists whose music was slowly disappearing. Although he does not consider himself an activist, the content of the music and traditional songs he produced was highly political, often referring to the 1860s war and the struggle for Circassian identity. “We wanted to show this music not for some foolish reasons, like nationalistic, but just because it’s cool music”. Regardless, in today’s Russia, where opaque laws are malleable to the despot’s whims, being associated with separatism is a dangerous endeavor. Undeterred, Mark and Alexey organized many shows and festivals. Although Moscow’s growing authoritarianism was on full display in Georgia in 2008 and in Crimea in 2014, It was only with the 2022 ‘special military operation’ that he seriously considered leaving Russia for good. From the onset, he thought about departing for Turkey or Armenia, but the prices skyrocketed due to the demand (over 5000 USDs for most flights out of the country [7]). He therefore mustered many more shows and events to raise further money.

The state of fear in the North Caucasus was far from baseless. He compared the Ukrainians with Circassians, telling me that: “In Russia, people were saying that Ukrainians were our brothers. But when the war started, and we saw what the Russians did to their “brothers”, we could not even imagine what they could do to us from North Caucasus”. A frighteningly bleak observation.

If at first his situation seemed to stabilize, with the war far from his hometown, the partial mobilization announced on September 21st ushered in a new era of panic. Barely a week into the draft, Russians were flocking to the nearest borders, most with no return plans. The Russo-Georgian border of Verkhny Lars, not far from Mark’s hometown of Nalchik, became the gateway to safety for Russian urbanites. His family hosted many of them on their way there. In the first week of October, Mark and Alexey made the decision to flee as well, leaving their families in Circassia as they were the only ones at risk of being drafted.

The extent of the exodus and the traffic jam incurred transformed a simple drive into a prolonged march for survival: Instead of a few hours drive, Mark would take 5 days by car and 40 hours on foot just to reach the border. In the initial days, confusion, misinformation, and contradictory statements led them to believe that a border closure was imminent. He remembered the second day as “in total limbo”. Their main concern, apart from a border closure, was that they would be denied entry into Georgia. To increase their odds, the two friends decided to buy a one way ticket from Tbilisi to Istanbul a week from then, as proof to the customs officials of the temporary nature of their stay in Georgia.

Walking up along the river in this rocky highland, Mark has a clear memory of the horde’s typology: “A lot of people from the big cities, especially from Moscow. People with money to travel, IT guys, people with diplomas”. It was hardly surprising – the first who were able to leave needed money, contacts across the border and to be highly informed of the situation in the news and on social media. A catastrophic brain drain, happening already since February, was now supercharged by the mobilization order. Computer scientists, economists, political scientists, biologists, historians – the list of disciplines goes on. In 2022, it is estimated that between 800,000 to 1.2 million Russians fled their country, of which 500,000 during September’s mobilization alone [8][9][10]. Putin, in full damage control, justified this emigration, “convinced that a natural and necessary self-detoxification of society like this will strengthen [Russia]” [11]. In a twisted way, the unintended consequence of this exodus was the dismantling of the Russian intelligentsia and dissenters whose precarious existence through systemic crackdowns was now reduced to nothingness. If there ever was a chance for an uprising, now no figurehead could lead it.

I asked him if he personally knew anyone who received such a chilling draft letter. “Yes, I know some people,” Mark said, “I know some who were hiding. I also know others who went to war because it was a way to make good money because in our region, you can’t make money, so people without strong principles enlist, the others hide or flee”. This is another reality in the federation: apart from the main cities, the rest of the territory is poor, and geographically too far from the main economic hubs. In that context, where the average monthly salary is 720 euros, one time bonuses for joining the military of up to 30,000 euros are tantalizing, if not life altering. The state also provides payment of 40,000 euros to injured soldiers. Additionally, in the case of death (a common occurrence when casualty rates on the front are estimated at over a thousand per day [12]), the Kremlin overheats the money printer with a myriad of handouts: 49,000 as a one time payment for the family, 49,000 as insurance payment, 30,000 as death benefit and yes, those figures are in euros, not rubbles [13]. Dubbed the “death economy” [14], this blood money is watered onto the population, stimulating consumer spending and artificially boosting growth (estimated to amount to 1.4 to 1.6% of Russia’s projected GDP for 2024, 7.5 to 8.2% of the federal budget expenditures for this year, and 3.4 to 3.7% of all consumer spending by Russians in 2023) [15].

After their exhausting 7 day journey, they arrived at the border. Circassians had the unpleasant surprise of having differential treatment – if not openly racist – from the rest of the ethnic Russians. Segregated in a makeshift camp on the side of the crossing, Mark recollected: “The worse thing is that for people who had their birth place in north Caucasus, the Georgians did not let you in like the other Russians, so there was a big camp for the north Caucasus people waiting for an interview with the police who were very rude”. They called this place room 222, which became infamous in the Caucasian community [16]. “We bought a ticket from Tbilisi to Istanbul and told them that we are going to stay only a few days in Tbilisi, and the policeman was saying that he will check if we use the plane tickets, If we don’t, he will deport us. He was just trying to scare us, and he was successful, we were scared”.

After crossing the border and obtaining a temporary visa, they both started working once again on their music, shows and events. Imagining however that crossing the border, a mere line on a map, would change their situation for the better would be foolish: the bear’s shadow is never far. Indeed, mirroring Russia, Georgia’s parliament had been passing increasingly harsher laws against political activists, labeled as foreign agents, on top of anti-LGBTQ bills prohibiting any pride events and flag display and censorship in books and movies [17]. Mark knew early on his stay in Georgia would be temporary, “because of the pro-Russian government, it became worse and worse to gather and organize events, […] a lot of my Georgian friends moved to Europe too” he told me. He finally succeeded in obtaining a humanitarian visa from the German authorities and promptly moved there. In September 2024 he managed to get a permanent resident status and a full time job at a university.

Looking back at the past two years, I enquired if he saw himself as one of this conflict’s many victims? His tone, until then monotonous, abruptly turned emotional, if not vexed: “I feel like it’s not right to take this stand, yes we are victims of this conflict too but the missiles are being launched towards the Ukrainian population, not us. People are dying there. It’s completely different. Even when the war started under the flag of our country, the first thing Moscow would say was that they are the victims of this conflict, forced to attack Ukraine. Ukrainians are mad about this. They are the true victims”. To consider this view broadly shared amongst Russian expatriates might be wishful thinking on my part.

Mark told me that on his way to the border, a local taxi driver shouted at him: “you are a traitor to the motherland”. How can he consider Russia his motherland? He does not want to die under a flag that is meaningless in his eyes . A state that has trampled over his cultural roots for decades, if not centuries. “Traitor”? Is refusing to wreak havoc in Ukraine really cowardice? Or rather is leaving all behind, relatives, friends, wife and kids to not kill under the white blue and red banner an act of great bravery? Although censorship and misinformation efforts of the Kremlin are trying to hide realities of the frontlines, Russians know what is unfolding behind “the ribbon”. Telegram provides the civilian population with a plethora of channels, all with direct feeds from the front line. The New York Times did an incredible piece on a Russian officer who, after being sent to the front line against his will, deserted. What transpired through this reporting was how the entire country sleepwalked into fatalistic passiveness: “apathy is a skill that requires practice over time” – Russians had plenty [18] [19]. Mark and Alexey’s singular act of defiance is something to look up to.

From Germany, they both are preparing the festivities of the label’s 10th anniversary, sharing their beloved music to an entirely new audience. May art soothe us all.

~

Sources:

[1]: Anatolii Chernysh, GLIMPSE INTO MOBILIZATION IN RUSSIA: OVERVIEW, METHODS AND PROSPECTS. (Ukrainian prism, 2024). retrieved from: https://prismua.org/en/english-glimpse-into-mobilization-in-russia-overview-methods-and-prospects/

[2]: Sergey Golubev, Macro‑mobility. Scooters and panic at the border crossing between Russia and Georgia.(Mediazona, 2022). Retrieved from: https://en.zona.media/article/2022/09/22/bordercrossing

[3]: N.n, The COMPLETE list of Russian tsars, emperors and presidents. (Russia beyond, 2021). Retrieved from: ttps://www.rbth.com/history/334065-complete-list-of-russian-tsars-emperors-rulers-presidents

[4]: N.n, Russian Federation. (Minority report group, 2024). retrieved from: https://minorityrights.org/country/russian-federation/

[5]: Valery Dzutsati, Circassians Express Indignation Over Monument to Tsar Alexander II in Sochi. (The Jamestown foundation, 2015). Retrieved from: https://jamestown.org/program/circassians-express-indignation-over-monument-to-tsar-alexander-ii-in-sochi-2/

[6]: Andrew S.Weiss, How Putin came to fear ‘’color revolutions”. (Foreign policy, 2022). Retrieved from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/11/05/russia-putin-color-revolutions-insecurity-ukraine-graphic-novel/

[7]: Megan Harwood Baynes, Draft-age Russians flee country as plane ticket prices soar and border crossings increase. (Skyt News, 2022). Retrieved from: https://news.sky.com/story/draft-age-russians-flee-country-as-plane-ticket-prices-soar-and-border-crossings-increase-12703643

[8]: Daria Talanova, The great Russian brain drain. (Novaya gazeta, 2023). Retrieved from: https://novayagazeta.eu/articles/2023/08/19/the-great-russian-brain-drain-en

[9]: Johannes Wachs, Measuring russian brain drain in real time. (BMC, 2023). Retrieved from: https://blogs.biomedcentral.com/on-physicalsciences/2023/06/26/measuring-russian-brain-drain-in-real-time/

[10]: Nicu Calcea, Russia’s tech brain drain in numbers. (Samizdata, 2024). Retrieved from: https://blog.samizdata.co/p/russias-tech-brain-drain-in-numbers

[11]: N.n, Putin warns Russia against pro-Western ‘traitors’ and scum. (Reuters, 2022). Retrieved from:

[12]: Eric Schmitt, September Was Deadly Month for Russian Troops in Ukraine, U.S. Says. (The New York Times, 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/10/us/politics/russia-casualties-ukraine-war.html#:~:text=U.S.%20and%20British%20military%20analysts,that%20was%20set%20in%20May.

[13]: N.n, Russia boosts army sign-up bonuses amid escalating frontline losses. (The Bell, 2024). retrieved from: https://en.thebell.io/russia-boosts-army-sign-up-bonuses-amid-escalating-frontline-losses/

[14]: Marie Jégo et Margaux Seigneur, « Un Russe mort rapporte davantage à sa famille qu’un Russe vivant » : comment l’« économie de la mort dope la croissance en Russie. (Le Monde, 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.lemonde.fr/international/article/2024/08/29/en-russie-l-economie-de-la-mort-dope-la-croissance_6298235_3210.html

[15]: N.n, Russia’s payments to soldiers and their families amount to eight percent of federal spending, study finds. (Meduza, 2024). retrieved from: https://meduza.io/en/news/2024/07/17/russia-s-payments-to-soldiers-and-their-families-amount-to-eight-percent-of-federal-spending-study-finds

[16]: Luiza Mchedlishvili, Tata Shoshiashvili, ‘A humiliating experience’: 4 days in limbo on the Georgian–Russian border. (OC media, 2022). Retrieved from:

[17]: Felix Light, Georgian parliament approves law curbing LGBT rights. (Reuters, 2024). retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/georgian-parliament-approves-law-curbing-lgbt-rights-2024-09-17/

[18]: Sarah A. Topol, The deserter. (The New York Times Magazine, 2024). Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2024/09/20/magazine/ukraine-russia-war-deserter.html?searchResultPosition=3

[19]: Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov. Alternate Reality: How Russian Society Learned to Stop Worrying About the War. (Carnegie Endowment for international peace, 2023). Retrieved from: https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2023/11/alternate-reality-how-russian-society-learned-to-stop-worrying-about-the-war?lang=en

[20]: Waiting at the border, generated by chatgpt

Leave a Reply